West: A Translation by Paisley Rekdal

Illuminating the marginalized histories of the American West

Rekdal’s hybrid poetry-essay book gave me so much food for thought, especially in these times. Its structure is inspired by an elegy a Chinese detainee at Angel Island carved into the walls:

Sorrowful news indeed has passed to me.I mourn you: on what day will your wrapped body return?Unable to shut your eyes, to whom can you tell your story?Had you known, you never would have made this journey.A thousand ages now hold the sorrow of a thousand regrets.Missing home, you face in vain Home-Gazing Terrace,your ambitions, unfulfilled, buried under earth.Yet I know death can’t turn your great heart to ashes.

Detainees at Angel Island were forced to live in cramped and unsanitary barracks for days, sometimes months, and even after their long detentions, many were simply deported. Some committed suicide. The author of this poem, who has since faded into anonymity, wrote it after discovering that their friend had met this end.

This elegy is unusual for its time, according to its translator, Dr. Fusheng Wu, who also worked with Rekdal on the research for this book. Poems written in regulated verse like this were typically autobiographical, but rather than speaking from the poet’s own experience, this poem imagines their friend’s perspective, now rendered inaccessible by death. Rekdal’s book is very much in the spirit of this poem as it imagines the voices of various people whose lives were impacted by the creation of the transcontinental railroad, and in doing so, exhumes the ghosts of the many anonymous workers who such a national project possible. Rekdal’s collection about the settling of the American West makes poems titled with each word or phrase from the Angel Island writer’s poem. Each of her poems have an accompanying note that provides historical context and flashes of Rekdal’s personal history to enrich the lyricism.

I appreciated just how thoroughly researched this book was. By piecing together archival material from maps to archeology, it showed me moments of Asian American history I had never heard of before — like the ghost town of Terrace, Utah, which once was home to a community of Chinese railroad workers. You can still find shards of centuries-old soy sauce bottles in the dirt. I learned that many Chinese railroad workers saw their time in the US as temporary and even had their bones mailed back to China after they died. The collection spotlights not just Chinese railroad workers, but also other groups whose roles in this history haven’t been properly recognized — African American railroad workers and porters, women telegraphers, the Native nations who resisted this further encroachment on their land and the Native workers who continue to maintain the railroads today. Rekdal also imagines the voices of railroad barons like Leland Stanford. (I was reminded at times of the ways Robert Hayden used archival material from the perspectives of the oppressor to imagine a history of the oppressed.) My favorite poem of the collection imagines the voice of Sui Sin Far, a half-Chinese, half-white journalist who wrote, among many things, cultural commentary about her journeys across the U.S. and Canada as a mixed race woman. The poem perfectly captures the unease and the defiance that come with asserting an identity and, ultimately, fashioning a self.

One of the most tragic and infuriating parts of our understanding of the American West is that we have very few primary documents from the workers themselves, the overwhelming majority of whom were people of color. As it stands today, we have no surviving documents from the perspectives of Chinese railroad workers. Not even one. “Regardless, the fragment of history remains a history,” Rekdal writes. Undeterred, she creatively uses what she has to read between the lines. A series of poems in the book draw from an English-Cantonese phrasebook some workers carried on them to ease their interactions with white people. The selection of phrases that the authors of the guide thought would be most useful to them is, it itself, very telling.

I’m really glad I read Rekdal’s collection as the Utah book in my #Reading50States challenge. And, though this is a history of the West that spans more than just Utah, it is fitting as my pick for this state because it was created in response to the 150th anniversary of when the final spike was driven into the transcontinental railroad in Promontory, Utah. It was made of solid 17.6 carat gold.

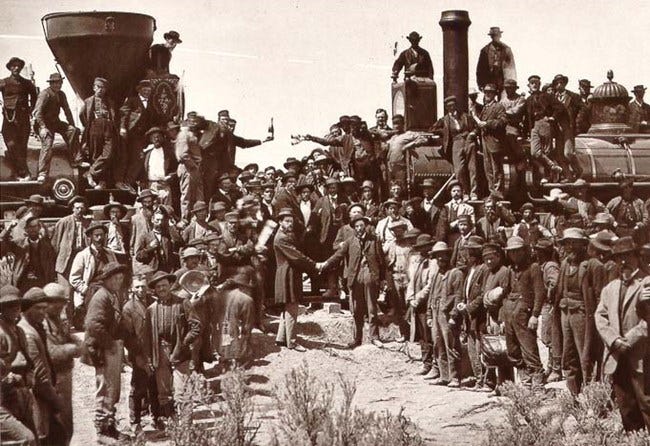

The famous photo of the Golden Spike Ceremony, taken in 1869, is so blatantly representative of our nation’s violent fantasy of the American West: that the land was theirs for the taking, the people were mostly white, and that seeking prosperity was justified no matter the cost. It couldn’t be further from the truth. Corky Lee famously gathered the descendants of Chinese railroad workers to recreate this picture, as one small but symbolic act of correction. In these times, I am grateful to the Paisley Rekdals and Corky Lees of the world for these essential acts of preservation and imagination.

I love that you spotlighted this book by Paisley Rekdal! I first read the West: A Translation website 4 years ago (https://westtrain.org/) before the book formally came out and it forever changed my understanding of Asian American history. After reading this, I'll have to read the full book!