On every Thursday night for just about a year, I worked part-time at a Hong Kong-style bakery. The menu shifts seasonally — mango sago in the summer, for example, and red bean soup in the winter — but from day one it has specialized in making daan tats, a pastry that is often the litmus test for the caliber of a Chinese bakery, according to chef and writer Tim Chin. For the uninitiated, daan tats are sweet egg tarts that are signature treats of Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Macau. The best daan tats, in my opinion, have flaky crusts and are filled with soft, melt-in-your-mouth egg custard that has been gently infused with vanilla, lemon, and/or cinnamon (the flavorings vary between regions). The golden little suns are heavily inspired by the Portuguese pastel de nata and the English egg custard tart but are a completely different, amazing pastry in their own way. I’ve eaten daan tats for as long as I can remember, and I’ve had them in almost every Chinatown I’ve ever visited. They’re notoriously difficult to make, so I joined this bakery to learn the details of the meticulous process, and what I got was also a window into the intricacies of running micro bakery and the dedicated people behind them.

Every daan tat crust was made completely from scratch with the best ingredients we could get our hands on and hand rolled into the perfect width. We maximized the lamination of the dough to have dozens of layers of perfect buttery, light crispiness. We made bolo baos filled with a coconut gai mei bao filling. Eating one of these fresh out of the oven is one of the best things I’ve ever had. As I spent hours molding the puff pastry dough into circles and scoring what would become the crumbly tops of bolo baos, I got into hours-long conversations with the fellow bakers. Sometimes we just fell into the rhythms of kneading, mixing, and baking in silence. The work was repetitive, but in a way that could become meditative, the only way real way to muscle memory and eventually mastery. Working at this bakery was the first job I had that was more physical than mental, and where I didn’t feel like I was a minority as an Asian American. As much as I relished this experience and will think of it for years to come, I don’t want to romanticize the real challenges of working, let alone owning and operating, a small bakery. It’s not something you get into for the money; everyone I worked with was drawn to this work primarily out of passion. On my last shift, just before the lunar new year, I taught everyone my red bean soup recipe so they could add it as a special winter product, which felt like a poetic culmination of my time there.

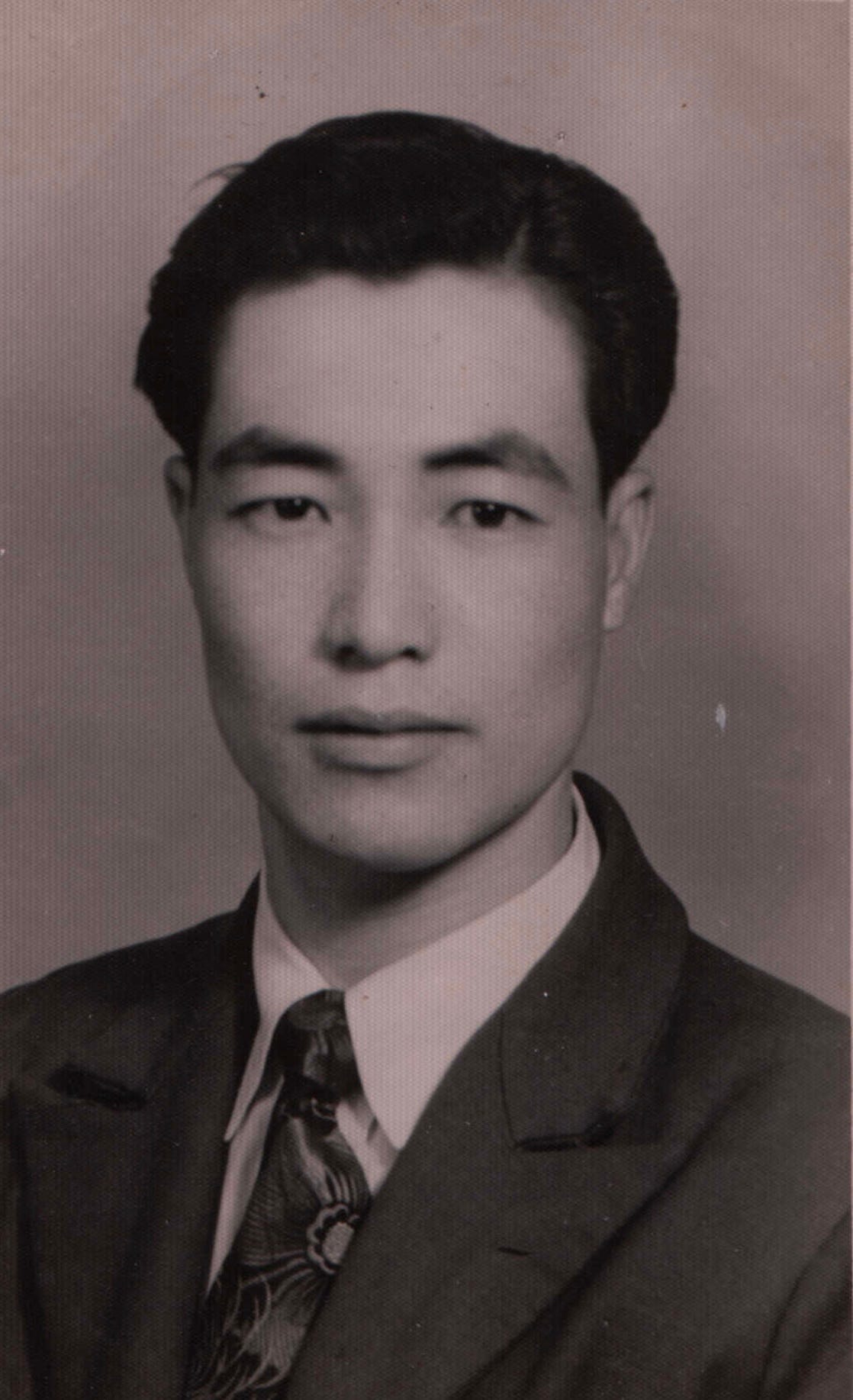

And then, while celebrating the new year at my uncle’s house with my family a week later, we made a huge discovery: my gong gong, who worked in a few different bakeries when he lived in Hong Kong in the sixties, had left behind a notebook of all the recipes he’d gathered throughout his life with the dream of opening his own bakery in the U.S. that didn’t pan out. It was sitting on my uncle’s shelf. Flipping through the yellowed pages of handwritten instructions, I felt like a scholar poring over a rare manuscript that felt immeasurably distant yet intimate. It’s been over a decade since he passed away. The gong gong I knew didn’t talk much when I knew him, at least to me, and rarely spoke about himself. The tableau that comes to mind is of him sitting in his usual armchair, flipping through the Chinese newspaper, just on the verge of a nap. Finding out about this long-ago dream was a revelation.

The task at hand now is to translate it. Showing the book to a friend, she picked out some of the words — “rice flour,” “mix”…and then she said, “why is the word ‘shirt’ in here”? A memory from years ago suddenly came back to me — that my cousin mentioned that one of our uncles would steam cheung fun using an old shirt to achieve those thin layers of rice noodle. Maybe he learned it from gong gong. It’s an old school method that I see less and less, even in Chinatown. I felt buoyant just from that discovery alone. This trip to the past was, of course, a path to understanding my family but also to a culinary tradition I’d been wanting to grasp for years.

That I’m now around the same age gong gong was then when he learned how to make baos and noodle doughs is not lost on me. When I made the daan tats and baos at this tiny midwestern bakery, was I unknowingly regaining his muscle memory? When I make his recipes one day, I want to recreate them exactly, or at least as close as I can get. What is legacy if not generational repetition? There might be more efficient methods out there for making cheung fun — but they’re not my gong gong’s. I feel something incredible and unnameable now that I know we shared the same dream.

SHANNON - this was beautiful. As someone currently working at an Asian bakery, you put into words perfectly the feeling of being a baker: the meditative repetitive-ness, the beautiful silence, as well as the real demanding reality of a physical job (aching hamstrings, being on your feet all day). Thank you for sharing this — and what a sweet discovery to find your gong gong's recipes.